Water From Your Eyes: Microtonal Indie-Pop

“Life is horribly dark right now. And yet, it is not unfunny.” Finding humor in fatalism is the ethos behind offbeat indie-pop band Water from Your Eyes. Comprising Rachel Brown and Nate Amos, the duo began collaborating in 2016 having found common ground in the serene yet somber sounds of Scott Walker and New Order. Drawn towards their experimental impulses, the duo’s debut album Long Days, No Dreams (2017) reveled in discordant, palpitating rhythms alongside absurdist, poker-faced lyrics grappling with the injustices of capitalism and personal strife.

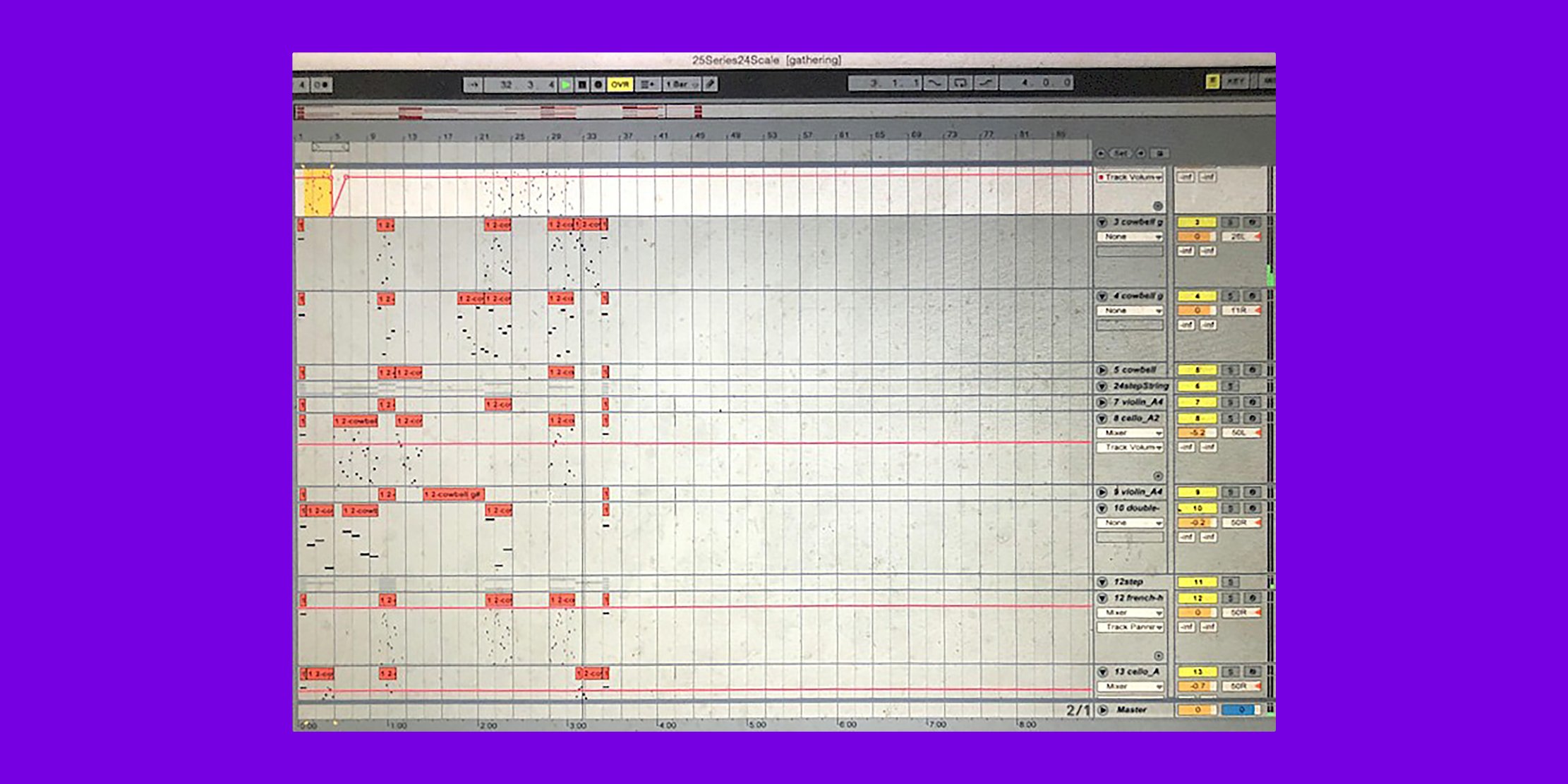

In an attempt to discombobulate the creative process, Amos has increasingly utilized Ableton to supervise his idiosyncratic approach to production. Water from Your Eyes’ fifth album Everyone’s Crushed offers more home truths, leaning further into the schism that lies behind their unique sound chemistry. Expanding on previous serial compositional and microtonal techniques, Amos’s use of Ableton’s stretch and sampling tools helps to create a geometric collision course of alien tonalities that divides the band from its indie-pop peers.

Your latest album, Everyone’s Crushed, claims to find “silliness in fatalism”. What are you fatalistic about and is satire Water from Your Eyes’ coping mechanism?

It’s not so much satirical as finding humor in what can be a humorless situation. A lot of the album was made during a period when I was having some health difficulties and didn’t really feel like there was much to laugh about, so the music and lyrics are very emotionally honest. The process is set up in a way that the music exists first and Rachel will react to a single line of lyrics that acts as some sort of prompt or launching point. In the past, the lyrics have always been a collaborative effort where, rather than be super-involved, I would prompt Rachel who would become the writer while I functioned more as an editor. With Everyone’s Crushed, Rachel set the lyrical tone in a way that was a little more extreme, to the extent that most of the starting points I provided were no longer the focal point of the song.

The track 14 is a good example of the dichotomy in your sound. It sounds like a love song but the music inverts that emotion. One might call it ‘beautifully ugly’.

Beautifully ugly is the way I thought about the song because, at first glance, the track is very pretty. Most of the music is composed using a series from a random number generator, so a randomly occurring beauty is surfacing from the twisted elements buried within it. That leaves the mood up to the interpretation of the listener, who may find it kind of frightening. Every line in 14 can be interpreted in a variety of ways and how it’s absorbed is very much influenced by an individual’s cumulative experiences up to the point at which they hear it.

It’s hard to know these days, but did you use real strings on the track?

I find that a lot of the sample packs that are computer generated sound really good technically but lack some of the imperfections that make live strings so interesting. 14 is therefore a combination of three different sampled elements - a giant, messy zip file of public domain samples taken from compositions recorded very hastily by real orchestras, an old, cheap Lowry organ and some sampled guitar feedback. I’m not recording directly into a sampler - I prefer to create sound libraries that are a combination of lo-fi cell phone recordings and hi-fidelity stuff.

There’s very little vocal processing on 14, which lends it a raw honesty that’s in-keeping the rest of the album…

It’s the one big difference between this album and the rest of our catalog. In the past, we did a lot of vocal layering to smooth things out - and that also applied to instrumental parts where there was a lot of double or triple tracking and much smoother production. This album is intentionally very jagged and exposed, and once the tracks were made it seemed natural to approach the vocal process in the same way with largely unprocessed, upfront takes. With the exception of True Life, this album is almost entirely based on single vocal tracking.

How important is the philosophy of serial composition to your music-making process and was that something you’d researched academically or through the observation of others?

My interest in serialism and microtonalism surfaced when I was transitioning from the previous Water from Your Eyes album, Structure. It was never something I studied in an academic setting, but I did a lot of research and through teaching myself how to use tone matrices I at least learned enough to find my own hack serialist methods and use them in a way that was creatively inspiring.

Do you see serialism as a way to counter writer’s block?

It’s more about forcing the writing process underground to make it a subconscious rather than conscious activity. Structure was very much written with the idea of discovering how to generate music in a way that was not creative. If you create madness and then try to make sense of that as an editor rather than a writer, you suddenly end up with all these basic building blocks that you never would have had discovered otherwise. For Everyone’s Crushed, the samples were laid out using the sampler in Ableton and often spliced and split onto two tracks in order to achieve a quarter tone process.

Is there a mathematical element to the process in terms of how you would typically approach serialism via the 12-note chromatic scale?

It depends on what you mean by mathematical. The idea of chromatic serialism, as I understand it, is that you have 12 notes in an order where no single one can be repeated until every other note has been played. If we’re talking about some sort of pattern imbalance relating to that order then, no, I just tend to make a ton of randomized patterns and wait for one that sounds interesting. When I’m working on a serial composition, most of the time the series itself will be generated on random.org and that part of it will always be random. What’s not random is the scale you choose to apply.

Can you give an example of your serialistic approach to specific tracks on the album?

The track 14 was all based off of a randomly generated series of notes, but rather than apply that to a chromatic scale I applied it to a major scale before creating all these weird, detuned microtonal scales in the background. For the track Barley, the series of notes that a lot of the sounds on the track are based off was a completely atonal 24-note series applied to a one octave quarter tone scale. Again, the series itself is generally random, but the way you choose to move forward is an instinctual reaction to how you want the music to feel emotionally. But that’s not real serialism – the whole point of serialism is to give structure to a composition that has no key, so I’m breaking rules there but it’s still a process for generating content.

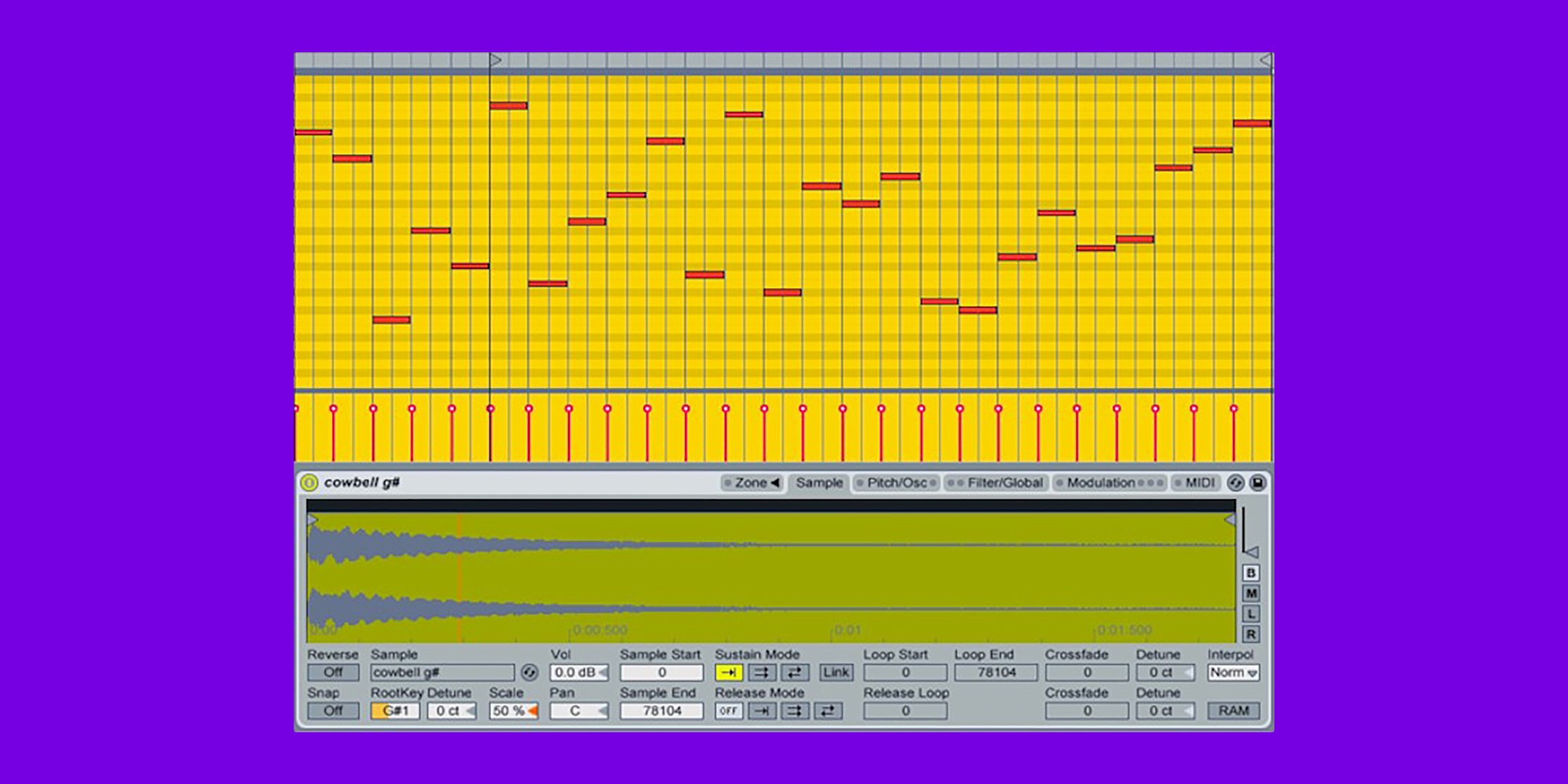

A component from the Water from Your Eyes track 2:27, from the album 33:44, showing a MIDI note display of a 25-note series meant to be in quarter tones.

Ableton Live sample display of the track showing the scale at 50%, thus translating into quarter tones.

You mentioned the track Barley as being a good example of how you created your own micro scales. Are those linked to the randomly generated notes that you’d already created?

That was something I thought about doing independently. I’d been listening to a lot of microtonal music but there’s no easy way to program things like that – you have to hack it. Maybe in newer software there’s a way to do it, but when it comes to quarter tone programming I haven’t found a way to turn an octave of MIDI notes into 24 notes rather than 12. Instead, I’d create multiple tracks, detune one by a quarter-step and translate between the two with a lot of scribbling down on pieces of paper to figure out ways in which they could be programmed. That was definitely something that had to be deliberately thought about and conceptualized.

What type of sounds did you apply that process to?

Barley has the same series of notes happening at a variety of speeds that were all programmed using a combination of sped-up violin samples, guitar notes I’d recorded, harp plucks and cell phone recordings of single piano notes. So I’m mostly sampling and programming, mainly because I’m not capable of naturally playing quarter tones on a microtonal guitar.

There also appears to be a lot of detuning of notes…

The pitch manipulation concept is kind of like an audio optical illusion. I do this sneaky thing where a series of notes would start as a randomly generated thing that I altered to make it seem like the sound was continually falling down in pitch. It’s not actually changing in pitch from repetition to repetition it’s just designed to feel that way. If I remember correctly, I spent a lot of time hanging out and cleaning my room with a Sheppard Tone [a sound consisting of a superposition of sine waves separated by octaves] playing in the background.

You mentioned that there’s a visual process behind how you make music. Do you therefore rely on visual tools to give you added tonal precision?

When it comes to the visual aspect of the sound design, I’m not frequently looking at analysers or visual representations of scales as much as trying to communicate or translate the emotional impact of visuals to audio and tend to look more towards painters rather than musicians to achieve that. When you take inspiration from a different medium it forces a certain amount of subconscious translation that’s inherently unique to every individual. For example, if two people said they’re going to make something inspired by a particular Flaming Lips song, they’d probably both come up with something that sounds kind of like that, whereas if they both say, okay, we’re going to sit down and make a song inspired by a painting, they would likely end up with totally different interpretations and creations.

Water from Your Eyes has never conformed to traditional pop or rock structures. Did you always want to make a statement about how you thought music should be made?

There’s a big difference between setting out to make something different and embracing something different when it happens. A lot of the music I made when I first started was an attempt to be conventional, but what it’s become at this point has been more of a natural development. Ultimately, we should just embrace whatever happens regardless of whether it sounds conventional or, for want of a better term, ‘out there’.

Follow Water from Your Eyes on Bandcamp and their website

Text and interview: Danny Turner

Band photo: Eleanor Petry